|

A shorter but also different view on comics that I wish to share:

The textual world assumes priority over other forms of literature. In this world, we privilege great works of literature

defined by particular eras, and then chart them in bibliographic records. One can locate a title from centuries ago, others

of which are similarly archived and, more recently, becoming accessible in digitized formats. We can also identify them by

genre, character and/or theme. Comics, however, remain largely on the periphery.

What markedly defines a comic is the admixture of image and text to tell a story; in the case of wordless comics, what

defines them as comics is the sequence of images to show a particular story (which is problematic when you consider that a

traditional museum display is similarly represented since the group of art pieces shown are not randomly assigned and usually

include captions, making them, very broadly defined, comics). Yet comics also define particular modes of storytelling and

can likewise be found subdivided among classifications of fiction and nonfiction, superhero and non-superhero.

Graphic novels, which denote novella-length comic books (in which the storyline is more cohesive, fuller and longer

than traditional comics), also equate with fictional stories. Nonfiction contributions by comics artists such as Marjane Satrapi

(Persepolis, Embroideries), on the other

hand, can now be found in the Biography section, though these are also graphic novels.

Part of the problem has been the increase in manga and related comics from Japan

and outlying areas, which are more extensively fiction. In the United

States, the market remains dominated by superhero comics, which are also fiction.

What is perhaps different today from even the late 1980s is that more traditional publishers like Pantheon

Books are starting to get into lines of serious comics, that is, nonfiction. For that

reason, comics published by Art Spiegelman (more known for Maus among mainstream

consumers), Joe Sacco (Palestine, Safe Area Gorazde), Joe Kubert (fax from sarajevo), and David B. (Epileptic)

are finding spaces in traditional (non-comics) categories.

At the

same time, it is not always easy to distinguish between fictional and nonfictional graphic novels unless these are explicitly

expressed (i.e., by the publisher, comics artist). There are also comics artists

whose works, though not entirely autobiographical, take their cues from the writers’ and/or artists’ (in the case

of collaborations) experiences.

More

important, one cannot always find earlier serious comics using traditional search engines. For example, I did not know about

Madison Clell’s autobiographical Cuckoo, which is marked as Biography/Psychology

(and not as a comic), until Maria at Last Gasp of San Francisco told me about it.

A Select List of My Comics

American Elf: the collected sketchbook

diaries of James Kochalka: October 26, 1998 to December 31, 2003. Top Shelf Productions, 2004.

Arnoldi, Katherine. The Amazing "True

Story" of a Teenage Single Mom. Hyperion, 1998.

Barry, Lynda. One! Hundred! Demons!

Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2002.

Delisle, Guy. Journey to Pyongyang.

Drawn & Quarterly, 2005.

Doherty, Catherine. Can of Worms. Fantagraphics Books, 2000.

Jason. Hey, Wait...Fantagraphics

Books, 2004 (2001).

Myrick, Leland. Missouri Boy. First

Second, 2006.

Ward, Lynd. Gods' Man: A Novel in Woodcuts.

Dover Publications, 2004 (Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, Inc., 1929).

|

|

|

Here are some ideas (abbreviated) that I wanted to

articulate at the 2005 Vernacular Colloquium Conference:

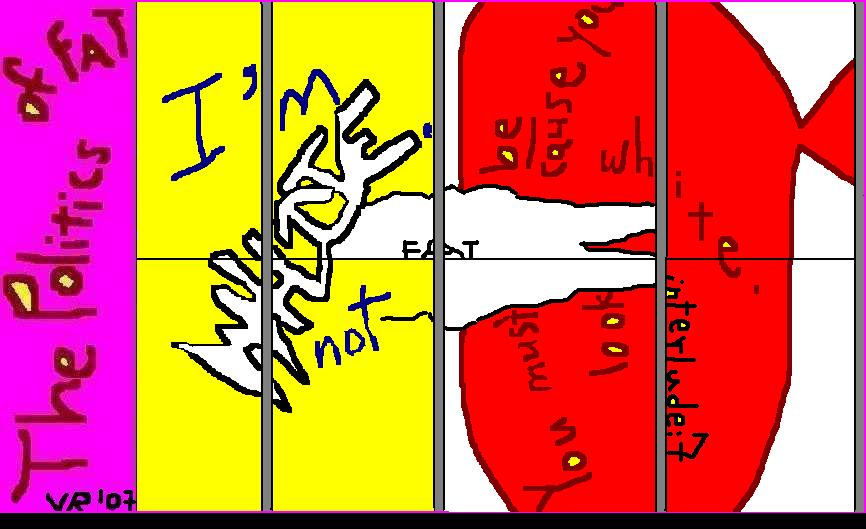

1. What is it about text and images that makes the comics format

unique? If a synergism exists between the languages of reading and seeing (or visualization, which also

has to be "read") that creates a particular experience between the writer/artist and reader, then what is the function

of that relationship? More important, what goes into the process of coding what a stranger understands about the personal

experiences of the autobiographical comic/graphic novel?

It is a problem, first, of making the image work with the text.

What is left out of the image needs to be found in the text and vice versa; otherwise, the comic risks being overtly

descriptive, taking on the form more of a picture book than a comic. If we understand a comic to be simply composed

of pictures and words, then the overgeneralization allows for any combination of images and text to be defined as a comic.

2. Photojournalism is more closely a comic than anything else,

especially when it features a montage of images designed around a specific story; however, a comic may also be comprised of

a single panel, which makes its categorization more difficult. The fine line between photojournalism and comics is the rope

game of the real versus the imaginary. Even so, you will sometimes find photos as part of the comics story (i.e., in Maus),

which seems to challenge the construction of the real. That is, while a photograph may reveal more similitude between the

actual and its reproduction (see Barthes), it, too, exposes a fictive product, one manipulable by the photographer and his

or her equipment.

3. The autobiographical comic, which proposes to uncover some aspect

of the writer/artist's past, too easily gets cast as a fiction. Despite studies in autobiography that challenge the truth

of personal history, the comics format invites skepticism because, despite McCloud's claim that iconography allows the reader

to assume the identity of the icon because its nonrepresentation intrudes a self-representation, the reader is unable to imagine

him- or herself as the "I" in the autobiogaphical comic.

That is due in part to the position of comics as fiction in

mainstream America. I think one reason Spiegelman's Maus gets so much academic attention is because it insists on

being nonfiction; its association with the phrase graphic novel also glamourizes it as novel and different, despite the

fact that a lot of comics, even when marketed as fiction (especially those of the underground), are autobiographically-based.

Although Maus did not revolutionze comics, it entered the publishing world at around a time when American comics

began to mature.

4. I do not mean to suggest that comics before Maus were

immature, but that the sophistication of the form as a medium for nonfiction is what makes the autobiographical comic today

undefined as a comic per say, which is why these can be found in bookstores under the term Biography than Graphic Novels.

The first story in Eisner's A Contract with God, a collection of four short comics stories, is based

partly on his experiences of losing his daughter to leukemia, but it is not nonfiction the way Maus is nonfiction.

Spiegelman did not simply write a story about his father, Vladek's, experiences in the Nazi camps, but he corroborated that

story with other survivor experiences, making Maus a larger nexus between biography and history.

5. Although the Vietnam War sparked a response in the underground

comix movement, that movement was also set off by the 1954 Comics Code, which created a different environment for

comics than the one that surfaced with the introduction of adult comics (see Sabin) in the 1980s. If the 1954 Comics Code

(see especially Kiste Nyberg) interfered with the evolution of comics, it is possible that what is observable about contemporary

comics today would have been true of comics in the 1960s - assuming the absence of the 1954 Comics Code. What I

am suggesting is that autobiographical comics then would have meant that they were part of the canon now.

© Vanessa

Raney 2005

|

|

|

|

I made these comments at different times to the comix listserv:

A book on the Staff Recommended shelf by Sonja Ahlers, titled Fatal Distraction (2004),

I have no idea what to make of it. It uses both image and text but I don't know if it's a collection of random sketches or

autobiograhical in some way or entirely fiction, etc. However, it raises questions about what defines a comic - does a comic

differ specifically because it has words and pictures? Because I know there are wordless comics, but these are sequenced.

Does a combination of random pictures and words fit the definition of comics? If you look at the history of comics, the later

prototypes (nineteenth century specifically, though McCloud (and I believe Eisner in his earlier work that precedes McCloud,

though McCloud gets a lot of the credit for suggesting a specific language of comics) also makes the argument that hieroglyphics,

too, could be construed as one of the earlier forms because of the way the pictures are sequenced - which almost makes you

need to accept them if you affirm that wordless comics are indeed comics) in which captions were added to image are legitimate

forms of comics, then is her work a comic? It makes me then wonder about picture books - couldn't these, too, be considered

comics? Can anyone help with this - is a comic defined more by form or what? Because then, couldn't picture books, illustrations

in the New Yorker and other periodicals, etc. be classified as comics?

The question of art or literature really reflects the ambiguous structure of the comic, which depends

on two simultaneous languages (Neil Cohn focusing on visual language) that, when the form really works and solidifies, depends

on both image AND text to tell the story. However, I've seen a lot of comics in which the images just show, not relate. However,

that is also true of a lot of literature, of which some is character-driven and others plot-driven, where you have conventions

in genre and literary writing, etc. The comic is no exception, but even then, it's confused. When the comic no longer gets

defined as a comic (for example, when I asked about Marjane Satrapi's Embroideries at Bookstop, I was told it was

Biography, not a Graphic Novel because for this store, graphic novels equated with fiction so what you saw in that section

were superhero comics, manga and Neil Gaiman, who's doing story), then you have a more pressing need to examine why certain

comics are being taken more seriously and appreciated as stories (as opposed to show and tell). I don't know where Eisner

fits in this, since I think it's fair to say that he's known more among comics readers/scholars/etc. as a serious comics artist

than among mainstream, though this may be changing.

Even so, the final product assumes a specific kind of definition that, when examined as an artifact that results from

specific social interactions and societal impulses, demands a different kind of analysis. However, it is the final label that

defines its processes more narrowly. What made comics more popular since Maus (and Dark Watchmen and the

one before that I can never remember offhand) - many (such as Roger Sabin) argue that it was the media hype of the word graphic

novel that commanded a different attitude, which I would argue is what's responsible for the current demand for graphic novels:

essentially comics made into books (novellas, for the most part). So now you see a wide assortment of comics serials being

republished as graphic novels, while works intended as graphic novels (long thematically-focused books) get jumbled in

with this. It reflects both an economic demand and a social context; comics are more "in" (so one could argue, though I don't

know how convincing this would actually be) because of the form. Even the superhero genre has found (maybe further than the

1980s) its way into graphic novel formats. Even newspaper comics are being thus recontexted.

|

|

|

|

|

|